Donbas, NATO, and the emerging battle against Economic decline

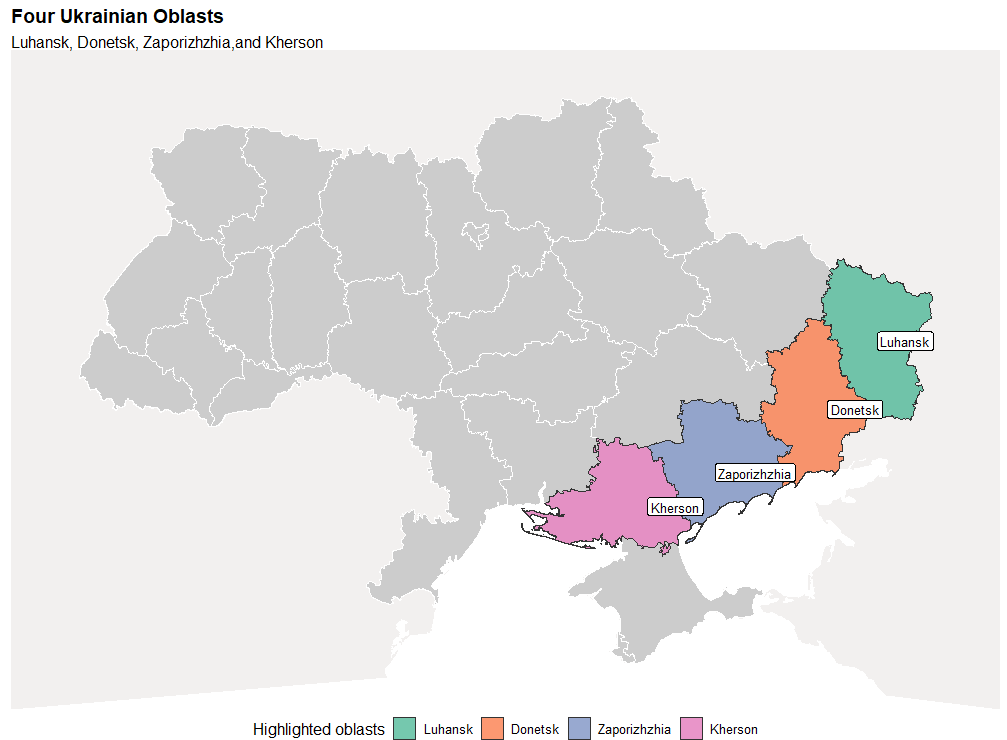

For more than three years of the Russia-Ukraine war, two issues have dominated the negotiation agenda: the status of the Donbas region (Luhansk and Donetsk) and Ukraine's relationship with NATO, particularly Article 5. The key question remains: are these genuine core war aims or merely bargaining chips?

The Donbas Region (Luhansk + Donetsk)

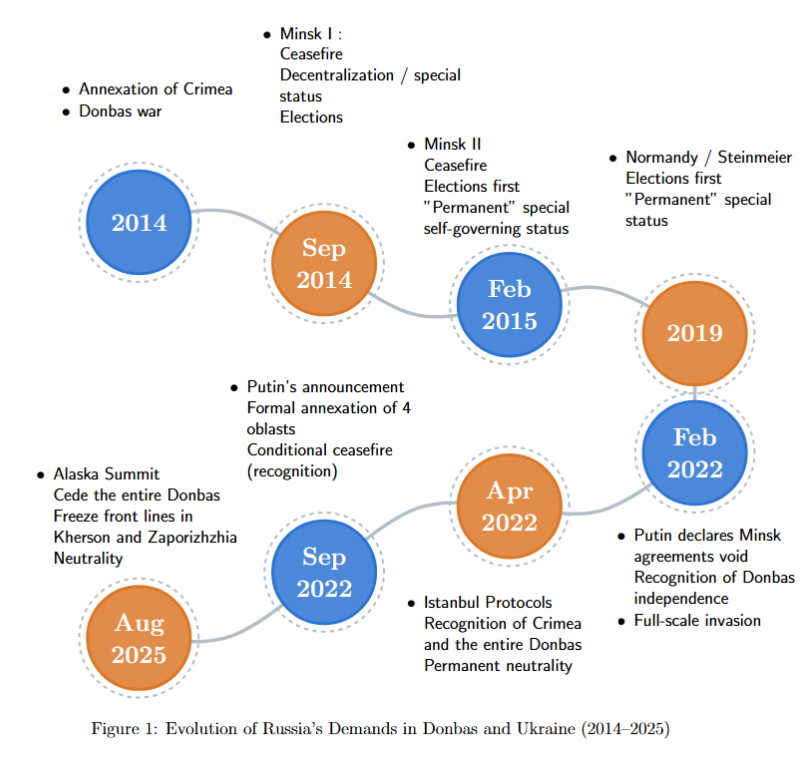

The conflict in Donbas has its roots in the EuroMaidan protests of November 2013, a mass movement against pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych. By February 2014, Yanukovych was ousted, which Russia condemned as a "Western-backed coup." Russia swiftly responded by annexing Crimea in March 2014 after a referendum, a region with a large ethnic Russian population. In April 2014, pro-Russian armed uprisings erupted in the Donbas region, sparking a war between Ukrainian forces and separatists.

Throughout the Donbas war and the Minsk I/II Agreements - as well as subsequent talks in the Normandy Format and under the Steinmeier Formula - Russia consistently pushed for political legitimacy for Donbas separatists, insisting on elections that would formalize regional autonomy. Moscow likely calculated that such elections would yield results comparable to the Crimean annexation referendum. This expectation was reinforced by demographics: according to the 2001 census, ethnic Russians made up nearly 40% of the Donbas population(Donetsk : 38.2% and Luhansk : 39%), the highest share outside Crimea(58.5%).

Yet, the number of ethnic Russians was not enough to guarantee a pro-Russian vote. According to the International Republican Institute's Public Opinion Survey (March 14–26, 2014), Ukraine's eastern regions bordering Russia and its western regions bordering Europe displayed starkly different orientations. The eastern regions referred to Donetsk, Luhansk, Kharkiv, and Dnipropetrovsk.

While 90% of people in the west supported joining the EU, 55% in the east opposed it. Similarly, 64% in the west favored NATO membership, whereas 67% in the east rejected it. Attitudes toward the EuroMaidan protests followed the same pattern: 71% in the west viewed them positively, but 71% in the east regarded them negatively. The most common response in the east was that EuroMaidan was a 'political coup d'état' - an interpretation echoing Russia's own characterization.

In this context, Donbas - home to eastern Ukraine's largest concentration of ethnic Russians - emerged as the focal point of resistance to the post-EuroMaidan trajectory of rapid political change toward the West. Much of the region sought pro-Russian autonomy, the demand actively backed by Moscow. Over time, however, the initial push for autonomy evolved into outright calls for annexation, deepening the conflict and shaping the trajectory of the Russia–Ukraine war."

The evolution of Russia's demands suggests that conquering all of Donbas was not an initial core aim. The goal seems to have expanded over time. Russia has failed to capture the entire region even after three years of war, which raises doubts about whether its demand for the whole of Donbas is truly non-negotiable. Unlike Crimea, the Donbas region has a smaller ethnic Russian population, and the initial goal was autonomy, not annexation. Therefore, the entire Donbas region seems to be a key bargaining chip, not a non-negotiable objective.

Neutrality, Demilitarization, and NATO's Article 5

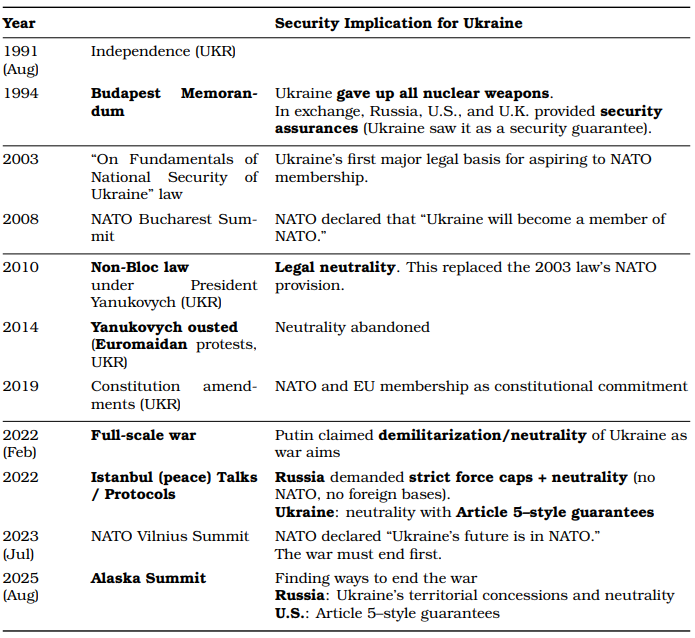

If the Donbas demand is primarily Russia's agenda, then NATO is a shared concern for both Russia and Ukraine. Since its independence in 1991, Ukraine has been pressured to maintain neutrality and not join any military blocs.

This policy shifted in 2003 for several reasons. Vladimir Putin's rise to power and his increasing influence over former Soviet states raised concerns. Ukraine's then-President Leonid Kuchma also favored a more Western orientation. However, the crucial factor was Ukraine's realization of the vulnerabilities of the Budapest Memorandum.

Ukraine had given up its nuclear weapons in exchange for security assurances from the U.S., UK, and Russia under the Budapest Memorandum. This proved to be a miscalculation. The memorandum was only a political commitment, not a legally binding defense obligation.

International relations theorist John Mearsheimer had warned that these Western security guarantees were not credible and that conventional weapons would be insufficient to defend Ukraine. He even argued that nuclear weapons were necessary for Ukraine's security and to maintain peace in Europe, predicting that neutrality would leave Ukraine vulnerable to Russia. Within the Ukrainian government, there was also a recognition that under the Budapest Memorandum, no one would actually fight for Ukraine.

In this context, Ukraine made a policy shift from neutrality to seeking security through NATO membership, formalizing its goal in legislation in 2003. Although a subsequent pro-Russian president, Yanukovych, reversed this, the policy of pursuing NATO and EU membership was reinstated after he was ousted. Ukraine's push for NATO membership became Russia's primary target, with Putin setting neutrality and demilitarization as key war aims - a stance he has maintained throughout the war.

Although NATO membership remains Ukraine's ideal goal, it is currently not a realistic option. Ukraine's pragmatic choice is to seek neutrality while also securing NATO Article 5-style guarantees. NATO's Article 5 is a collective defense clause that considers an attack on one member an attack on all, prompting allies to take "necessary" action. However, Russia opposed any collective defense commitments, including NATO-style guarantees.

After the recent Alaska Summit, U.S. special envoy Steve Witkoff stated that Putin had agreed to allow Ukraine to receive Article 5-style security guarantees from the U.S. and European allies, calling it a "game-changing" concession. If Russia truly agrees to such guarantees, it would indeed be a significant shift. But as always, the devil is in the details.

The precedent is instructive. In April 2022, during the Istanbul talks, Russia proposed a 'Treaty on Permanent Neutrality and Security Guarantees for Ukraine.' This draft required Ukraine to adopt permanent neutrality, renounce NATO membership, and drastically limit its armed forces and equipment - essentially leaving the country nearly disarmed.

While Russia did agree that Ukraine could join the European Union, the treaty's security guarantees came with a catch: they mirrored NATO's Article 5 in form but not in substance. The guarantors - listed as the U.S., UK, France, China, and Russia - would hold veto power over any defense assistance to Ukraine. In effect, Russia would retain control over whether Ukraine could defend itself.

This raises critical questions: in Putin's newly signaled acceptance of Article 5–style guarantees, who exactly would serve as guarantors? If China and Russia are included, and especially if they are granted veto power, the arrangement would amount to little more than a 2025 version of the Istanbul Protocol.

By contrast, if non-NATO states are included as guarantors without veto rights, can such guarantees truly replicate Article 5? Even NATO's own clause does not mandate automatic military intervention, but because its members are geographically bound and share security interests, the collective defense incentive is strong. That incentive is far weaker for non-NATO guarantors, and the outcome could look dangerously similar to the Budapest Memorandum - political assurances without credible defense commitments.

This leads to a larger strategic question: if Russia accepts U.S. and European Article 5–style guarantees, does NATO membership still need to remain a non-negotiable objective for Ukraine? To answer this, one must look beyond the headlines to a demand Russia has consistently emphasized but receives less attention in Western discourse: demilitarization.

Putin has repeatedly stated that the war's original purpose was to address the 'root causes,' by which he means blocking Ukraine's NATO accession and eliminating Western military influence along Russia's borders. For Moscow, therefore, the central objective is not merely preventing Ukraine from joining NATO but fundamentally curtailing its military development through cooperation with the West.

If Ukraine's defense capabilities were restrained under Russian terms, Article 5–style guarantees could become a negotiable issue, since Ukraine would in practice be unable to act on them. This, however, would leave Ukraine's security dependent almost entirely on external powers.

European leaders appear to grasp this hidden dimension of Putin's offer. In the wake of the Alaska Summit, their statements have repeatedly stressed that there must be 'no limitations' on Ukraine's armed forces or its military cooperation with Western partners. In other words, while headlines focus on Russia's supposed concession, Europe remains wary of the deeper strategic intent: to freeze Ukraine's military vulnerability while dressing it in the language of security guarantees.

Accordingly, Russia's indication of willingness to accept Article 5–style guarantees should not be interpreted as evidence of a substantive convergence between Russian and Ukrainian positions on NATO - the central issue of the war.

Any genuine concession of this kind would necessarily hinge on the precise institutional design and implementation details, which may themselves generate new points of contention. In this sense, future negotiations could prove even more protracted and difficult than battlefield developments. The Korean War provides a relevant historical parallel: of its three years, nearly two were consumed by drawn-out armistice negotiations.

Russia Holds the Upper Hand in Negotiations - But Economic Pressures Are Closing In

Given Russia's advantageous position, one might assume that Moscow is relatively unconcerned with the protracted nature of negotiations, instead prioritizing the pursuit of its core objectives while employing the talks as a means of exerting strategic leverage to secure additional concessions from Ukraine on the battlefield.

The Alaska Summit hinted at a strategic recalibration, where once non-negotiable issues suddenly entered the bargaining space. The rapid progression from discussions of a ceasefire to the possibility of ending the war, coupled with Russia's apparent concession on Article 5–style guarantees(by the U.S. and Europe), suggests that internal pressures within Russia may be reshaping its approach.

Let us turn to the Alaska Summit, where important signs of change emerged in the composition of the Russian delegation. This was a highly consequential meeting between President Putin and President Trump, convened to address the Russia–Ukraine war - an issue at the heart of acute confrontation not only between Russia and Ukraine, but also between Russia, the United States, and Europe.

Among the five key figures accompanying Putin, three were leading figures from the economic sphere: Andrei Belousov, Kirill Dmitriev, and Anton Siluanov.

- Sergei Lavrov : Foreign minister

- Yuri Ushakov : Foreign policy adviser

- Andrei Belousov : Defense minister

- Kirill Dmitriev : Russian Direct Investment Fund chief

- Anton Siluanov : Finance minister

Andrei Belousov, currently serving as defense minister since 2024, is a relatively new appointee to the position. His background, however, is not in defense. Trained as an economist, he previously headed the Ministry of Economic Development and served as a presidential aide on economic affairs. With the exception of just over a year as defense minister, his career has been overwhelmingly focused on economic policy.

Among the three economic figures, the most noteworthy is Kirill Dmitriev, CEO of the Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF). Since the beginning of President Trump's term, Dmitriev has frequently appeared in negotiations related to the war. The RDIF functions as Russia's sovereign wealth fund for foreign direct investment, established to attract international capital into the Russian economy and to strategically support sectors such as infrastructure, energy, and natural resources.

Dmitriev also has strong ties to the United States: he studied at Stanford and Harvard and previously worked at Goldman Sachs. Few could be better positioned to facilitate economic cooperation with the U.S. His presence at the summit signaled a distinct economic focus in Russia's approach. Moreover, he has long emphasized energy development in the Arctic as a Kremlin priority. Although issues such as Arctic energy were not part of the Alaska Summit's official agenda, his involvement offers important clues to Russia's broader strategic intentions.

Moscow now appears eager to bring economic concerns to the negotiation table sooner rather than later. Its concession on Article 5–style guarantees - once framed as a non-negotiable demand - may represent less a shift in security policy than a strategic maneuver to create space for discussions on economic issues with the United States.

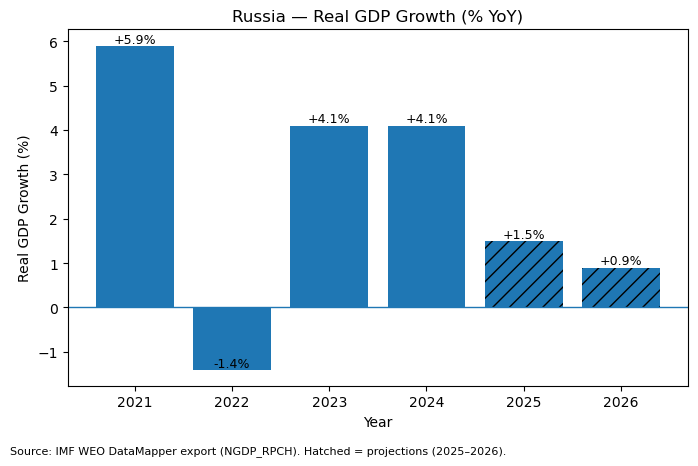

Why would Russia, which had prosecuted the war with determination despite extensive sanctions, suddenly signal readiness for a policy adjustment? The answer lies in the mounting strains within its own economy.

The year 2025 marks a critical inflection point: for the first time since the war began, significant economic vulnerabilities have become visible. Against most expectations, Russia had previously sustained robust growth of over 4 percent, buoyed by expanded trade with China, Turkey, the UAE, and neighboring states, as well as by large-scale state support for the military sector. These factors helped soften the impact of sanctions and insulated the economy in the short term. That insulation is now eroding. Growth has slowed sharply under the combined weight of declining oil prices, a widening fiscal deficit, persistent inflation, soaring military expenditures, and acute labor shortages.

At the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum in June 2025, Economic Minister Maxim Reshetnikov acknowledged that the economy stood 'on the brink of recession.' Although intended as a warning rather than a definitive forecast, his remarks underscored a new reality: in 2025, Russia is waging not only a war in Ukraine but also an intensifying struggle against economic contraction.

This backdrop helps to explain why Putin's five-person delegation to the Alaska Summit included three senior economic officials, signaling that Moscow increasingly views its wartime strategy through the prism of economic sustainability.

Simplifying the Analysis Through a Game-Theoretic Lens

Until now, the core issues in negotiations over the Russia–Ukraine war have centered on the Donbas oblasts and NATO. Beginning this year, however, an additional factor has entered the equation: Russia's looming recession. How, then, might bargaining over the resolution of the war unfold under these circumstances? While countless variables must be taken into account, a simplified formal model can still offer useful insights into Russia's strategy as the dominant actor on both the battlefield and at the negotiating table.

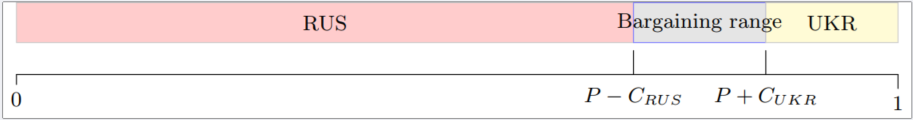

The bargaining model of the Russia–Ukraine war can be represented in a simplified payoff diagram. In this framework, P reflects Russia's expected probability of victory(or standardized payoff), while C denotes the costs of war. Thus, Russia's reservation value is therefore P - (Russia's cost). Since the current situation favors Moscow, the area representing Russia's share (RUS) is larger.

Ukraine, conversely, receives the payoff from the opposite side of Russia's outcome. As the costs of war increase, Ukraine's reservation value decreases, making its expected value P + (Ukraine's cost) in the diagram.

P lies within the bargaining range. If both sides reach an agreement at some point within this range, Russia and Ukraine can each secure a payoff greater than what they would obtain by continuing the war (that is, more than the respective RUS and UKR areas). Thus, a deal can be struck within the bargaining range. For Russia, however, certain issues - such as Ukraine's neutrality and demilitarization - fall outside the bargaining range, since they are treated as non-negotiable.

By contrast, Article 5–style security guarantees appear to lie within the range, making them a potential focus of negotiation. In practice, this means the bargaining is likely to revolve around different variants of Article 5–style guarantees, with the details determining the eventual outcome.

As the agenda setter, Russia holds the initiative. Moscow can present Ukraine with a demand package, 'X'. If 'X' lies outside the bargaining range and cuts into Ukraine's share, Kyiv will reject it. If 'X' falls within the range, Ukraine will weigh it against its current expected payoff before deciding whether to accept. In a simple static model, Russia will typically place 'X' at the far-right end of the bargaining range - the point that maximizes its own payoff. This, in turn, becomes the equilibrium outcome of the static game.

In reality, however, the situation is considerably more complex than a simple static model. Since Russia is negotiating with both Ukraine and Western powers, the uncertainty surrounding the bargaining game is amplified.

More importantly, the model must now account for dynamics. As Russia faces a looming recession, its costs are likely to rise sharply over time. The repercussions of the recession will affect not only the broader Russian economy but also its military capacity, thereby altering the payoffs in fundamental ways.

In the diagram above, as Russia's mounting costs rise over time, the bargaining range widens accordingly. At the same time, Russia's expected payoff from continuing the war declines. This means that from Moscow's perspective, securing a bargaining deal this year could yield a higher payoff than achieving the same deal a year later. From Moscow's perspective, the longer negotiations drag on, the less favorable its payoff becomes.

From a bargaining-theoretic perspective, Russia's rising costs have lowered its reservation value and expanded the feasible set of agreements, making settlement more likely. The shift of once non-negotiable issues into the bargaining range illustrates how changing material conditions - here, the onset of recession - alter the structure of payoffs and redefine the space of possible agreements.

Russia is now fighting on two fronts: the war in Ukraine and a mounting battle against economic decline. With recession eroding its resilience, time is no longer on Moscow's side.

References

Alaska Beacon. (2025, August 15). Anchorage summit appears to be part of Russia’s ongoing hybrid war. https://alaskabeacon.com/2025/08/15/anchorage-summit-appears-to-be-part-of-russias-ongoing-hybrid-war

Associated Press. (2025, August 15). Putin agrees that US, Europe could offer NATO-style security guarantees to Ukraine, Trump envoy says. https://apnews.com/article/trump-witkoff-ukraine-russia-putin-war-048aa829a69b4020ca368577bfe18aee

Business Insider. (2025, June). Putin's war-fueled economy is 'on the brink' of recession, minister says. https://www.businessinsider.com/russia-on-brink-recession-inflation-economy-minister-putin-2025-6

Hilgenstock, B., and Ribakova , E. (2025, July 16). Why Russia’s economic model no longer delivers. Peterson Institute for International Economics. https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/2025/why-russias-economic-model-no-longer-delivers

International Monetary Fund. (2025). World Economic Outlook Database: Real GDP growth (annual percent change), Russian Federation [NGDP_RPCH]. IMF DataMapper. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO

International Republican Institute. (2014, April). Public opinion survey of Ukraine, March 14–26, 2014. https://www.iri.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/201420April20520IRI20Public20Opinion20Survey20of20Ukraine2C20March2014-262C202014.pdf

Mearsheimer, J. J. (1993). The case for a Ukrainian nuclear deterrent. Foreign affairs, 50-66.

NATO. Collective defence and Article 5. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_110496.htm

New York Times. (2024, June 15). Ukraine-Russia Peace is as Elusive as Ever. But in 2022 They were Talking. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2024/06/15/world/europe/ukraine-russia-ceasefire-deal.html

Reuters. (2025, July 3). Putin tells Trump he won’t back down on goals in Ukraine, Kremlin says. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/putin-tells-trump-he-wont-back-down-goals-ukraine-kremlin-says-2025-07-03/

The Guardian. (2025, August 15).US-Russia talks on Ukraine: who’s who in the delegations to Alaska? https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/aug/15/who-are-the-us-and-russian-delegates-meeting-in-alaska-to-discuss-ukraine-putin-trump

The Guardian. (2025, August 16). Zelenskyy to fly to Washington as Merz says US ready to be part of Ukraine security guarantees – as it happened. https://www.theguardian.com/world/live/2025/aug/15/trump-putin-alaska-meeting-summit-news-updates

Ukrainian Census. (2001). All-Ukrainian population census: National composition of population. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. https://web.archive.org/web/20111217151026/http://2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua/eng/results/general/nationality/

Yost, D. S. (2015). The Budapest memorandum and Russia's intervention in Ukraine. International Affairs, 91 (3), 505-538.