The Threshold of Decline and Transition: America at the Crossroads

Toynbee's Creative Minority and Dominant Minority

In A Study of History, Arnold Toynbee examines the rise and fall of civilizations. He proposes a cyclical framework for civilizational development and identifies a key concept for understanding decline: role reversal. According to Toynbee, a civilization grows and flourishes through a challenge-and-response dynamic, which is led by a "creative minority". This group is composed of innovative and energetic leaders who successfully respond to challenges and, in turn, inspire the "uncreative majority". The majority imitates the creative minority and follows their lead.

However, when this minority loses its creative vitality, it transforms into a "dominant minority". At this stage, it attempts to maintain its position and privileges by force rather than by inspiring the population. The majority no longer imitates the minority. Instead, a new phenomenon occurs: the dominant minority, having lost its creativity, begins to imitate the manners, morals, and behaviors of the majority. This is what Toynbee calls role reversal.

In essence, Toynbee identifies a critical moment in a civilization's decline: when the leading group, which has historically solved challenges through creativity and its own high standards, loses its core identity and begins to lead through coercion. The moment role reversal occurs - when the dominant minority starts to imitate the uncreative majority - the influence of the leading group becomes inverted.

If Toynbee's critical moment is a qualitative concept, then the tipping point proposed by Ferguson is a quantitative one.

The Ferguson Limit

Across empires from Rome to imperial China to modern states, there has been a longstanding link between financial strength and military capacity. Fiscal power, more than any single factor, underpins a great power's geopolitical influence.

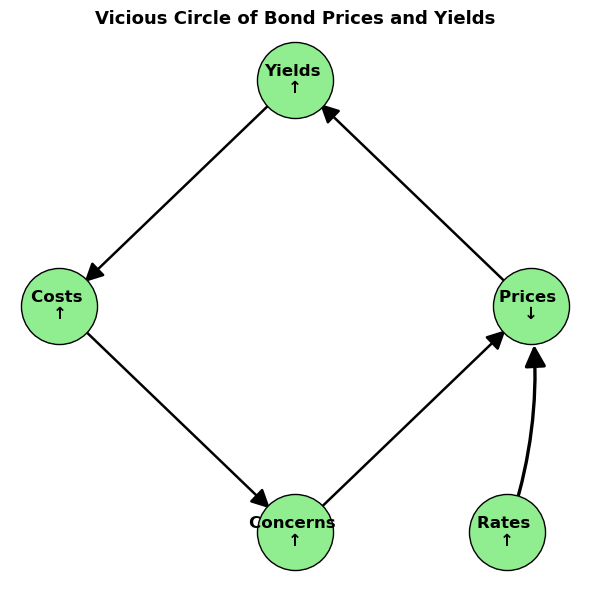

When a nation's debt continues to grow, an escalating debt burden can consume not only the country's revenue but also its available resources, unless interest rates decline. This financial deterioration can trigger a vicious cycle. As financial instability increases, investors will demand higher interest rates on new bonds. Consequently, the price of previously issued bonds with lower interest rates must fall to remain competitive. This drop in bond prices causes their yield (fixed payment of the bond / market price) to rise, which in turn becomes the new perceived market interest rate. This increase in borrowing costs raises concerns about the government's ability to repay its loans, a risk that drives bond prices down further and intensifies the spiral.

The gravest danger emerges when interest rates rise above the pace of economic growth. At that point, revenues generated by economic growth are consumed by debt servicing, leaving the state squeezed by severe budgetary constraints.

The government begins to face pressure from both the market and the political sphere. A significant portion of a nation's budget includes discretionary spending, but borrowing costs are non-discretionary. To cover the non-discretionary costs of debt servicing, an embattled government must identify and cut other budget items. While the government may need to implement austerity measures, such policies carry substantial political costs, including exacerbated political polarization, public dissatisfaction, and discontent among supporters, which can lead to dissension within the political elite. To minimize these severe political consequences, governments must find solutions to the debt crisis. Historically, as Ferguson points out, such political bargaining often leads to cuts in military spending.

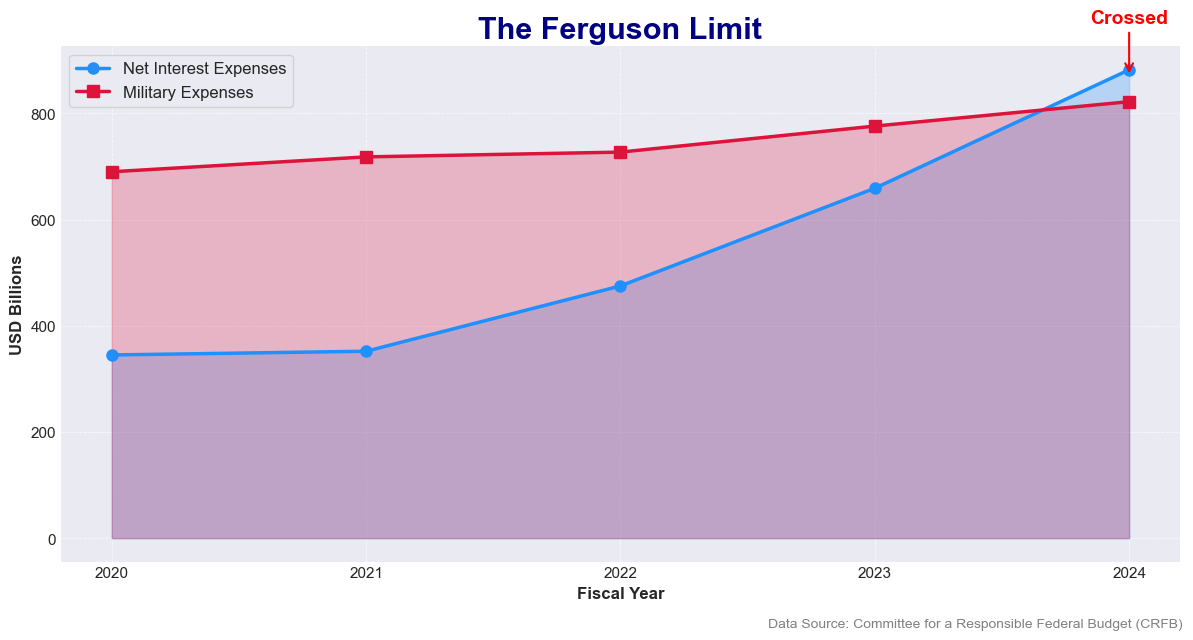

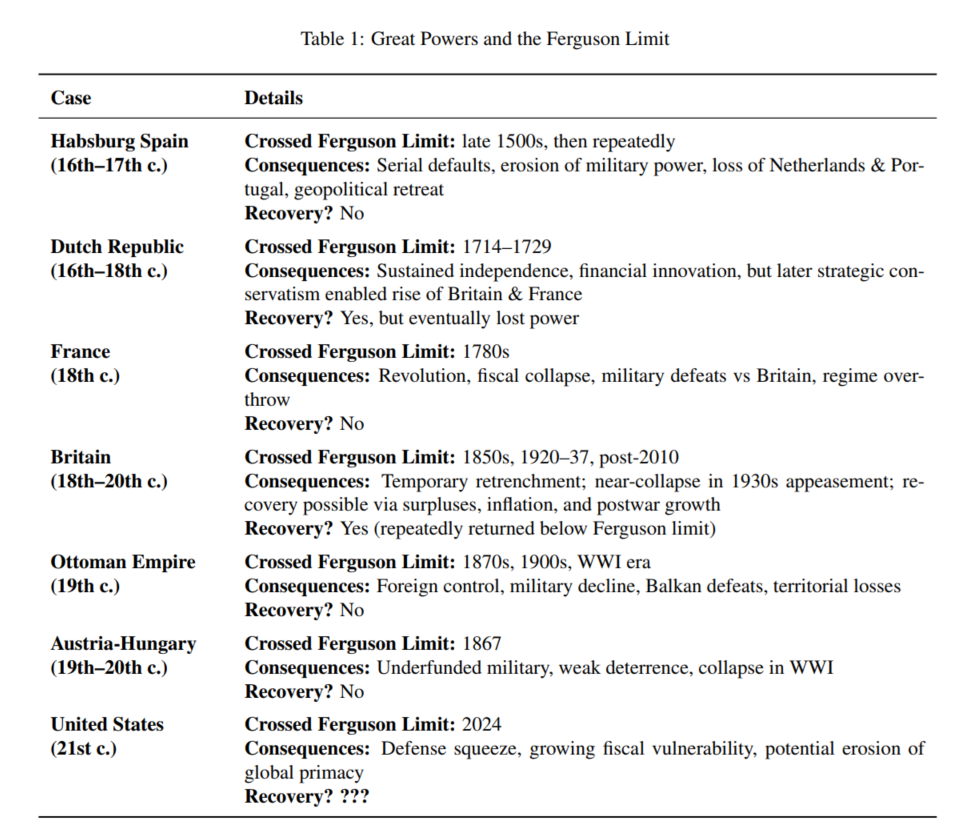

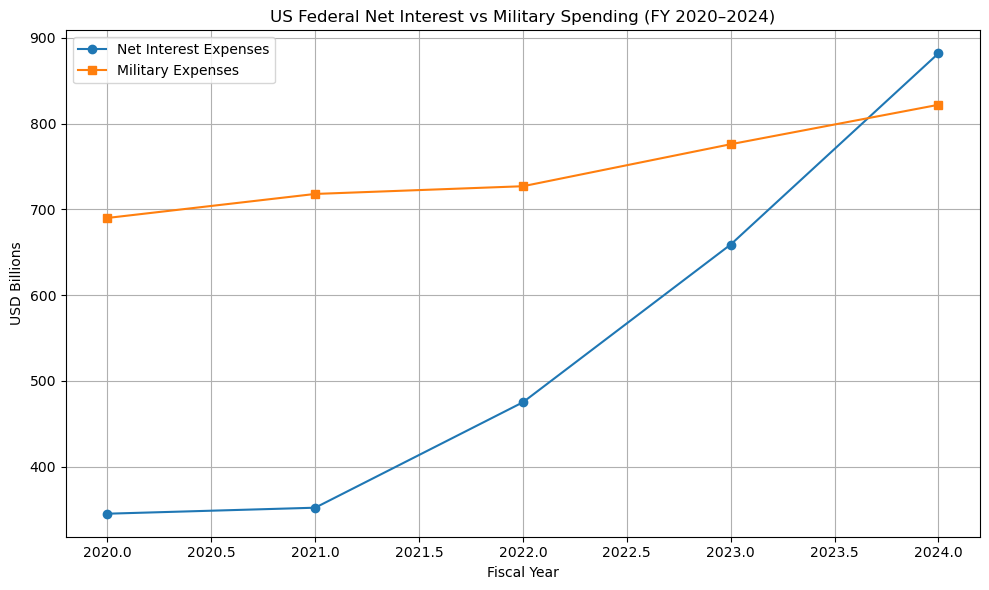

The Ferguson Limit is the critical threshold where a great power's borrowing costs surpass its military spending. This point marks heightened vulnerability, as resources are absorbed by debt rather than by military preparedness. While there isn't a direct causal relationship between military spending and borrowing costs, history suggests that crossing the Ferguson Limit is a "useful predictor" of a great power's decline and a "useful indicator" for policymakers to initiate a strategic shift.

As demonstrated by the historical cases in Table 1, when borrowing costs persistently outweigh defense spending, great powers experience a loss of military readiness, an erosion of deterrence, increased vulnerability to rivals, and domestic instability. This often leads to the decline of great powers throughout history. Thus, Ferguson's Law can be summarized as: a great power that spends more on servicing debt than on defense risks losing its great-power status.

In 2024, U.S. interest payments surpassed defense spending. If current trends continue, interest expenses are projected to double the defense budget by 2049. Given the observed historical pattern, a sustained crossing of the Ferguson Limit typically precedes geopolitical decline unless it is corrected by productivity growth, fiscal reform, or strategic retrenchment.

As mentioned, the Ferguson Limit can be a useful predictor of decline, but also a useful indicator for policy change. In 2024, this indicator has already signaled the need for a shift. Do the current policy changes in U.S. tariffs and fiscal policy align with a strategic turning point that can lead to a recovery from the Ferguson Limit?

Dalio's Big Cycle

Ray Dalio argues that the rise and decline of great powers over the last 500 years have followed a predictable pattern, which he calls the Big Cycle. He identifies three distinct cycles that drive the fate of great powers throughout history: the debt and capital markets cycle, the internal order cycle, and the external order cycle. By analyzing the Big Cycles of various great powers, Dalio finds that the destiny of a great power is always determined by these three cycles.

During the rise phase, the three cycles are characterized by favorable conditions such as low debt, small wealth gaps, and a peaceful global environment guided by a dominant power. However, during the decline phase, the three cycles are characterized by a debt crisis, polarization, and a rising rival. These downward or declining phases represent the challenges that a great power must face and solve.

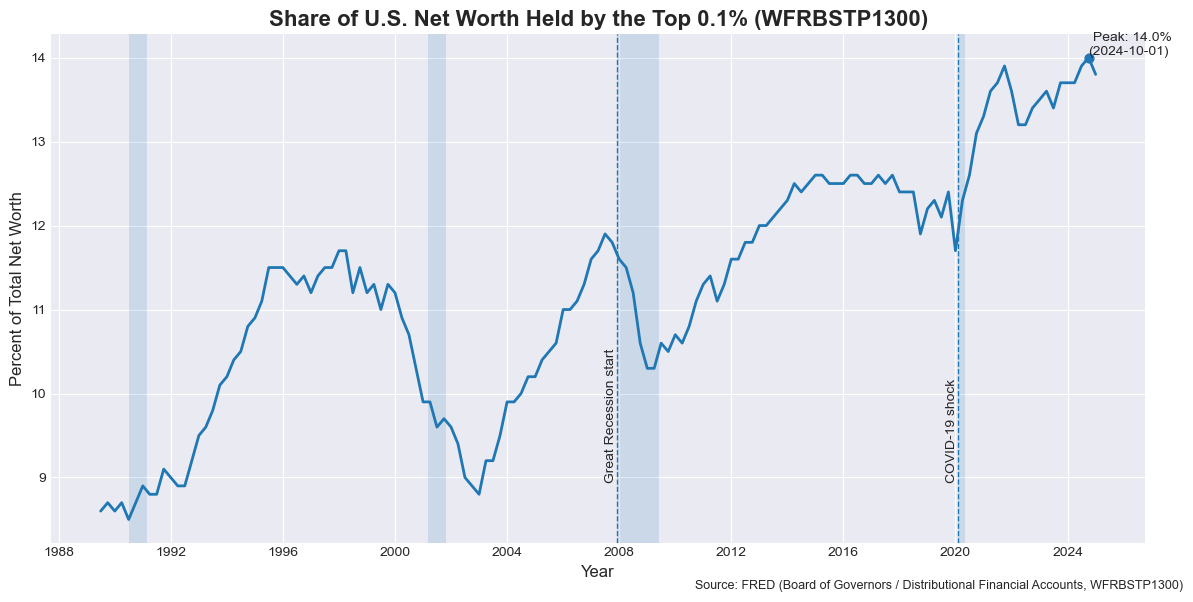

Let's apply this to the United States today. In terms of debt, the nation has already crossed the Ferguson Limit. For its internal order, polarization is intensifying. Wealth gaps have widened sharply. By 2024, the top 0.1% controlled 14% of national wealth.

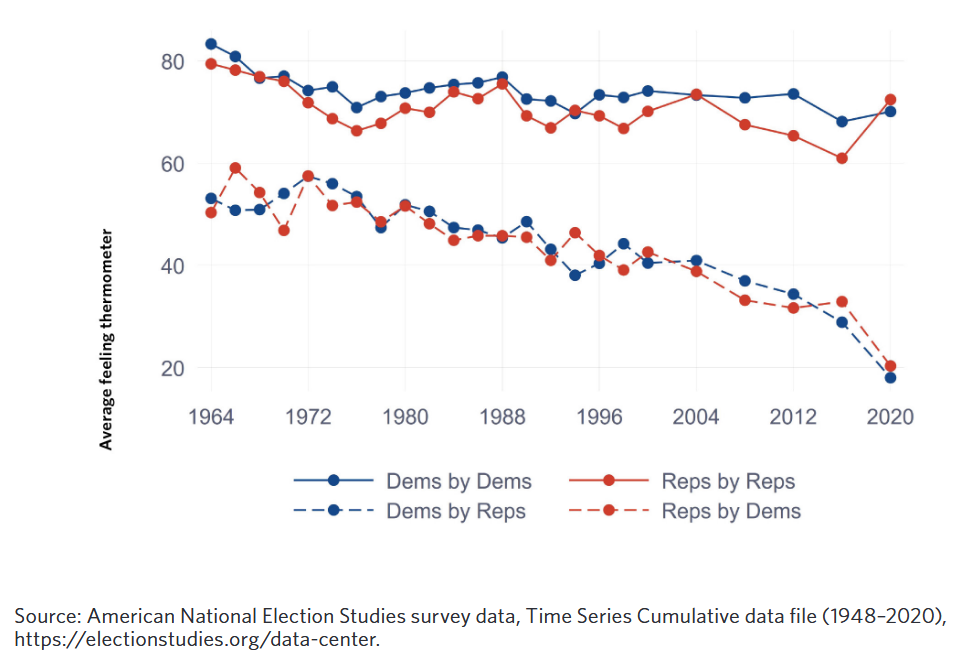

Furthermore, the American public is affectively polarized. Kleinfeld notes that affective polarization has been increasing steadily since the 1980s, driven by a growing dislike of the opposing party. The gap between preference for one's own party and aversion to the opposing party has become more severe over time.

Regarding the external order, the challenge from a rising China looms large, and it is questionable whether the U.S. can successfully deal with its rival. Oh identifies three goals of the current U.S. administration's tariff policy: (1) narrowing the trade deficit, (2) trimming the fiscal deficit, and (3) counterbalancing competitor China. However, at this point, the goal of containing China seems to be fading away. While the tariff policy has been effective as a beggar-thy-neighbor policy against friendly nations, its potential for success against the rival is increasingly in doubt.

At the Crossroads: Role Reversal?

Does this mean America's fate is sealed? Not necessarily. Cycles are predictable, but they are not destiny. Unlike other great powers in their decline phase, the U.S. retains immense advantages: technological leadership, financial dominance, global military reach, and - crucially - the dollar's role as the world's reserve currency.

The question is, how will the U.S. respond to the signals from Ferguson's Law and the Big Cycle? How will it handle the challenges it faces in this downward phase? Will it slide further into decline, or seize the moment to restructure and launch a new phase of order? Will it cede its place to the rival? These are the challenges for the next decade.

Ferguson argues that only a "productivity miracle" could bring the U.S. back from the Ferguson Limit. Oh believes that the current period may be the beginning of a transitional phase from the Pax Americana, which has lasted for more than 30 years since 1991, to the formation of a new world order. It's impossible to know whether this will be a new phase of rosy prospects or a completely new, uncertain order.

Whether through a productivity miracle or innovative restructuring, the U.S. might demonstrate its resilience as a great power. But can we have a positive outlook when facing the challenges at the start of this transitional phase? It will be difficult to answer this question by relying on historical patterns alone, as the future is not predetermined. Recalling Toynbee's framework provides a valuable perspective on this difficult question. With warning signals flashing, is today's U.S. still functioning as a "creative minority"? To me, it seems rather that we are witnessing the onset of role reversal and the consolidation of a "dominant minority."

References

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2025), Net Worth Held by the Top 0.1%, retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, August 16, 2025.

Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. (2024). Do we spend more on interest than on defense?.

Dalio, R. (2021). Principles for dealing with the changing world order: Why nations succeed or fail. Simon and Schuster.

Ferguson, N. (2025). Ferguson's Law: Debt Service, Military Spending, and the Fiscal Limits of Power. Hoover Institution, February, 21, 1.

Kleinfeld, R. (2023, September). Polarization, democracy, and political violence in the United States: What the research says. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Oh, Y.J. (2025, July 28). Tariffs Don't Tell the Whole Story. Public Debt and Market Interest Rates Do. The Geopolitical Economist. Medium.

Toynbee, A. J. (1987). A study of history. Oxford University Press.