Tariffs Don’t Tell the Whole Story. Public Debt and Market Interest Rates Do

Two Beggar-thy-neighbor policies

The U.S.’s current tariff policy ostensibly pursues three goals: (1) narrowing the trade deficit; (2) trimming the fiscal deficit; and (3) counterbalancing competitor China. Yet, as of July 26, 2025, the third objective appears to have been sidelined, making it doubtful that the United States can prevail in a tariff-driven trade conflict. China has been dumping its overproduced goods, made with subsidies, at low prices to U.S. allies and friendly nations. This threatens industries in those countries that compete with China. Ironically, the US tariff policy, rather than helping these allies, makes it even harder for them to compete with China. Consequently, US allies and friendly nations are inadvertently caught in the crossfire, enduring the effects of ‘beggar-thy-neighbor’ policies from both Washington and Beijing. A “beggar-thy-neighbor policy” refers to an economic strategy where a country attempts to improve its own domestic economic conditions by measures that inherently harm its trading partners.

Dual Magic (1): How the Dollar and Economy Grow Stronger Amid Trade Deficits

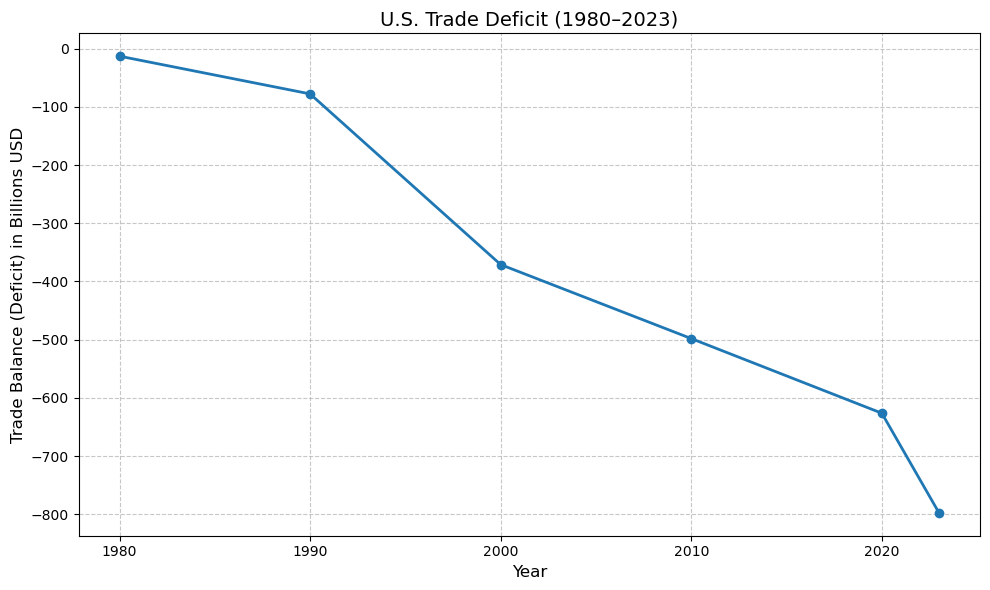

In December 2024, the U.S. trade deficit expanded to $98.4 billion. While trade deficits were modest in the 1980s, they began to swell significantly in the 1990s. This period coincided with a profound shift in the global order. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 reshaped the post-World War II international landscape. Although opinions may vary on when the “Pax Americana” truly began, the period after 1991 can be seen as its definitive onset. Under this regime, cross‑border trade and investment became more secure and long‑term oriented than ever before. Developed nations channeled capital into developing economies — especially former communist states with low labor costs. This era also ushered in the ability to transport manufactured goods more securely across vast distances.

A series of transformative changes unfolded under the banner of globalization. In 1994, the Uruguay Round, involving 125 countries, aimed for substantial reductions in tariffs and non-tariff barriers to trade. This was followed by the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995, an intergovernmental organization that succeeded the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) to set the rules for global trade. The WTO’s objective is to foster a more stable, predictable, and open global trading system by lowering trade barriers. Alongside the WTO, bilateral and multilateral Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) — special deals designed to make trading goods and services easier and cheaper — also proliferated. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), for instance, was an FTA between Canada, Mexico, and the United States.

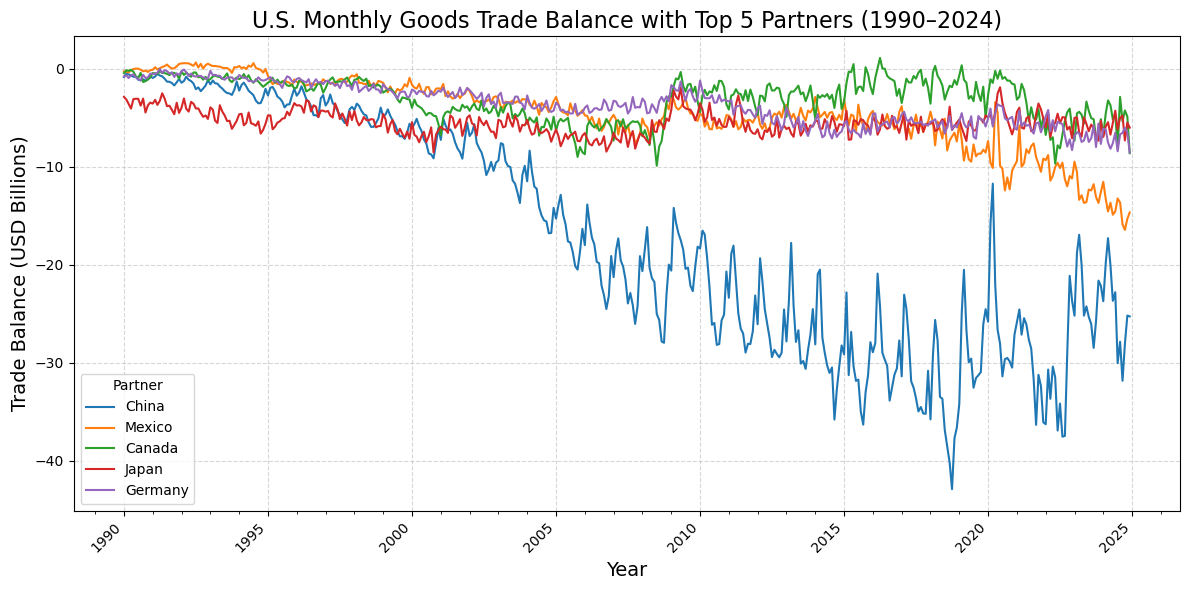

In 2001, China acceded to the WTO. The Clinton administration was a major proponent of China’s entry. This accession completed a structural transformation of the global economy, shaped by global supply chains and trade agreements. It effectively opened the floodgates for low-cost manufactured goods, with imports exerting downward pressure on inflation.

An examination of the U.S. goods trade balance reveals that China accounts for an overwhelming proportion of the goods deficit. Mexico, while significantly behind China, ranks next. China and Mexico, representing a large share of the U.S. trade deficit, can be seen as emblematic of the US-led global economic structure — specifically, global supply chains and the availability of low-cost manufactured goods. Crucially, this reflects the market choices of American consumers, empowered by access to diverse and affordable goods.

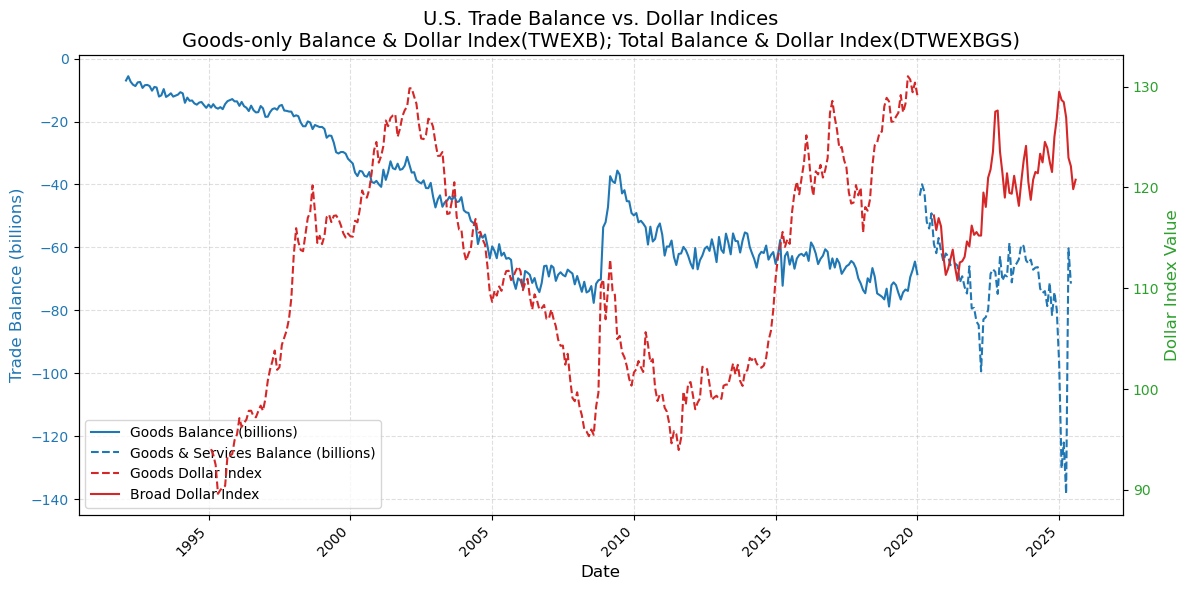

Typically, when a country faces a large trade deficit, its currency depreciates. This naturally leads to a decrease in imports and an increase in exports. If a trade deficit persists without currency depreciation, it usually precipitates a foreign exchange crisis. However, the United States has sustained massive trade deficits for extended periods without ever experiencing a foreign exchange crisis. While there have been several economic crises (attributable to oil shocks, the dot-com bubble, the housing bubble, and the pandemic), none were foreign exchange crises. The U.S. has never undergone a situation akin to the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

Even more intriguing is the fact that despite persistent trade deficits, the value of the dollar has actually appreciated. What is impossible for other countries has become a reality for the United States. This paradox — where trade deficits coincide with currency appreciation and economic growth — is enabled by the “dollar” itself. The U.S. can issue dollars as needed, while other countries require the dollar for trade and for the stability of their own currencies, as it serves as a safe-haven reserve currency during crises. In this environment, the dollar’s value climbs, allowing American consumers to purchase imported goods even more cheaply. This, in turn, can further widen the deficit. If, for any reason, the U.S. trade deficit were to disappear, it would likely be due to a recession or a fundamental shift in the global economic system, such as the U.S. losing its monetary hegemony.

The current trade deficit is a phenomenon created by the structure of the global economic system and the dollar’s hegemony. Can tariffs genuinely resolve this? My view is ‘no.’ The gains from tariffs, relative to the sacrifices to the current economic system, are not substantial. The increased cost and complexity of importing goods are not solely borne by trade partners; American consumers shoulder a significant portion of this burden.

During President Trump’s first term, given China’s state subsidies to its industries, tariffs had the effect of shifting some of the burden onto China. However, the situation is vastly different now. Following the pandemic-induced recession and the Russia-Ukraine war, major economies are experiencing slowed growth. China, in particular, is facing warnings of economic stagnation and potential crisis, far from its previous robust growth. Without a transfer of the burden, it is American consumers who will directly bear the cost.

Dual Magic (2): The Unrelenting Slide in Interest Rates — and the End of the Enchantment

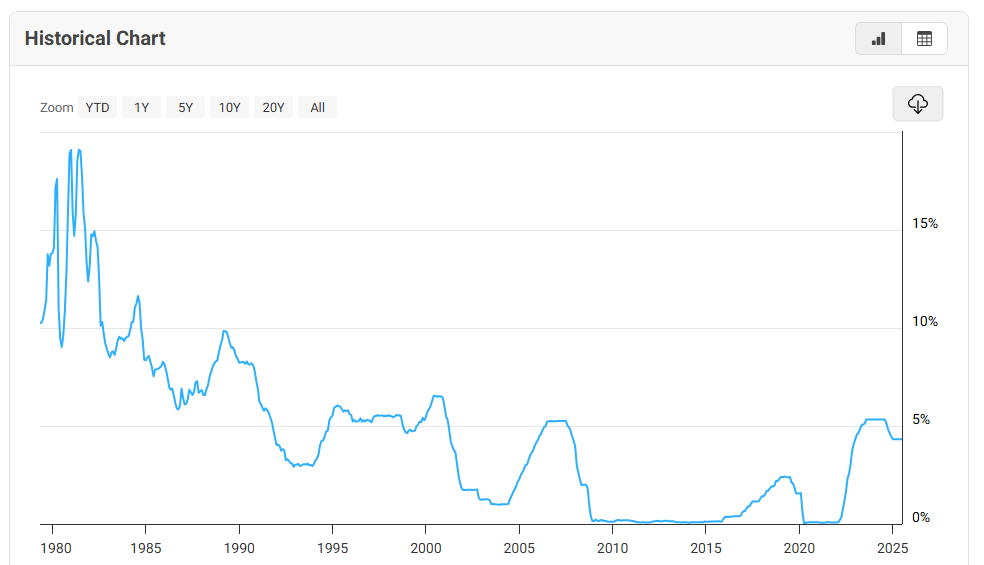

Interest Rates and Inflation

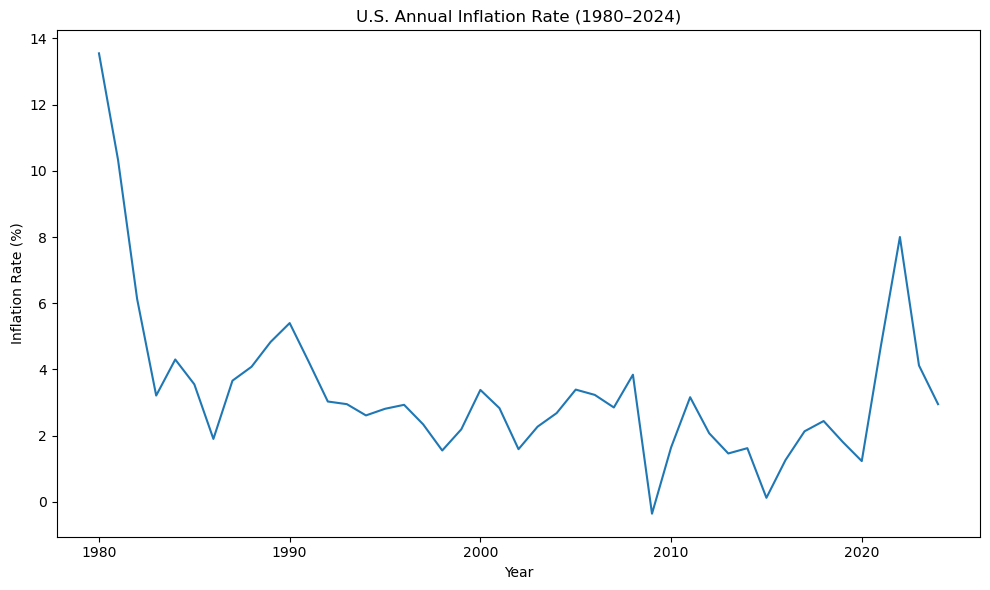

The U.S. federal funds rate has been on a sustained downward trend. Falling interest rates typically correlate with rising inflation. Therefore, a prolonged decline in rates might imply persistent inflationary pressure. However, despite the continuous drop in the federal funds rate since the 1980s, inflation has remained relatively stable. If price stability can be maintained, sustained interest rate cuts can stimulate continuous economic growth. Low interest rates facilitate investment, make it cheaper to finance homes and cars, and generally boost asset prices and the stock market. Despite this, concerns about inflation remained minimal.

While concerns about inflation grew after the significant fiscal spending and low interest rates implemented by the Federal Reserve in response to the COVID-19 recession, Fed Chair Jerome Powell famously predicted inflation would be temporary and soon wane. This demonstrated how the relationship between interest rates and inflation had seemingly weakened. (https://apnews.com/article/inflation-health-coronavirus-pandemic-business-6e7c813472a3eb706e0cdafe305c1477)

What allowed interest rates to fall without a corresponding rise in prices?

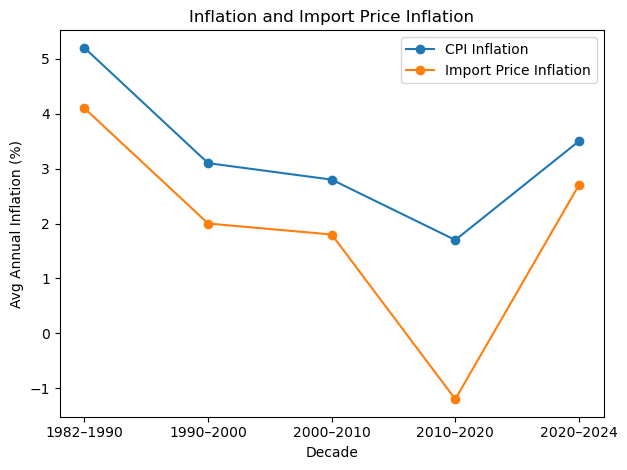

The answer lies in the import of low-cost goods, which contributed to the U.S. trade deficit. Within the global trade order established by the WTO and FTAs, countries like China competed vigorously in the U.S. market on price. As a result, American consumers benefited from consuming goods imported from around the world at remarkably low prices. The Inflation and Import Price Inflation chart clearly illustrates the disinflationary pressure exerted by these inexpensive imports. During the recession following the 2008 financial crisis, even as the Fed and government injected massive amounts of money into the market, prices remained stable while the economy recovered — a period that seemed magical.

However, the magic of the global economic structure that began in 1991 appears to be nearing its end. The disinflationary pressure created by imports largely dissipated after the liquidity was unleashed following the COVID-19 recession. Just as Cinderella’s magic fades at midnight, returning her to her original state, the relatively straightforward policies of the Fed and government under that spell are now confronting significant complexities.

(De)Coupling of Fed Policy and Market-Determined Interest Rates

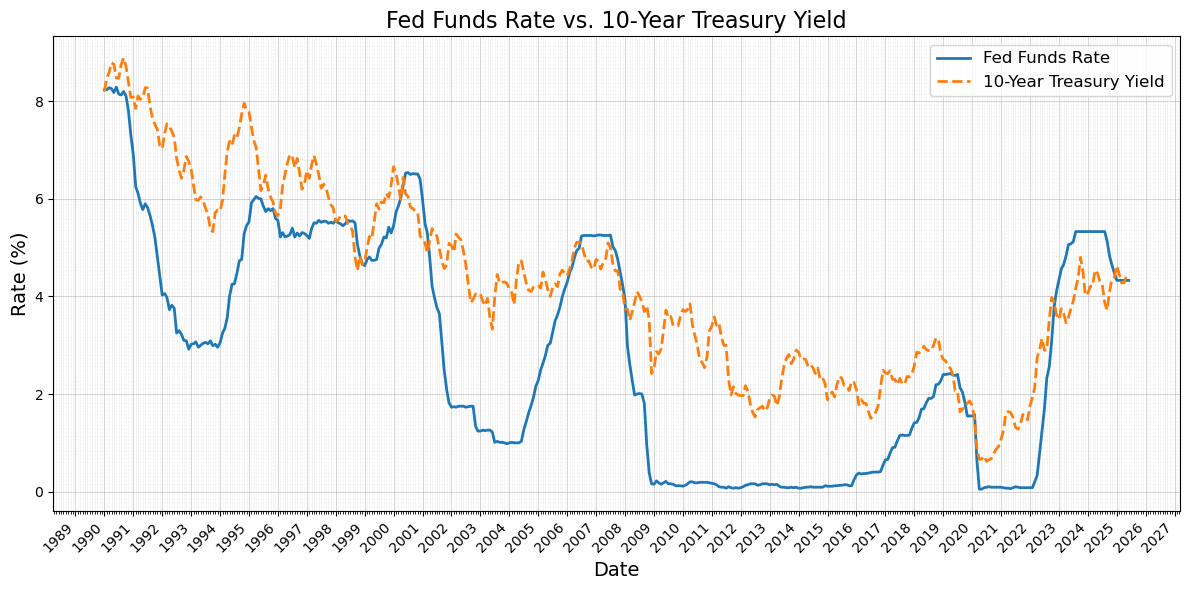

While the Federal Reserve can control short-term interest rates, its control over market-determined rates is limited. Even if the Fed wishes to maintain low rates, market-determined rates, such as the 10-year Treasury yield, do not necessarily follow the Fed’s lead. Their relationship can decouple. Indeed, in September 2024, the Fed lowered interest rates, but the 10-year Treasury yield actually increased.

During the recession following the 2008 financial crisis, as the Fed maintained low interest rates, the 10-year Treasury yield also declined. While low rates can sometimes lead to a “liquidity trap” where the Fed’s policy rate loses influence over market rates, this was not the case during that period; market rates also remained low.

The magic that prevented the decoupling of policy and market rates and allowed for a stable, low-interest-rate environment was “Quantitative Easing (QE)”. By directly purchasing government bonds in the market, the Fed supplied money to the banking system while simultaneously pushing down market interest rates. This unconventional policy was employed during the recessions following the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic.

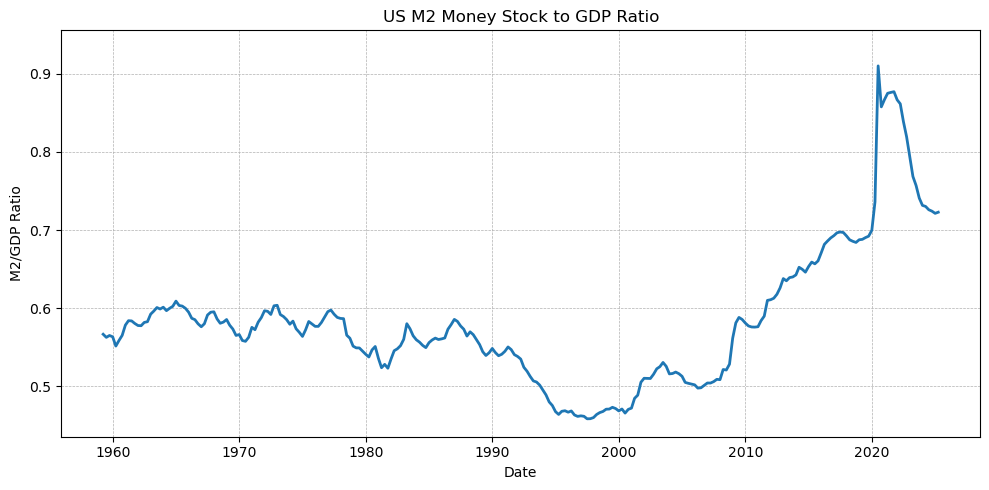

The era of consistently falling interest rates, which lasted for the past 40 years, is now drawing to a close. Even with some lingering disinflationary pressure from imports, the sheer volume of liquidity in the system is immense. M2 Money Stock to GDP ratio shows levels previously unseen, exceeding 0.6 and even reaching over 0.9. While there’s no fixed baseline for this ratio, comparing it to past economic crises and recoveries clearly indicates an exceptionally high level.

In this situation, the option of using QE to prevent a decoupling of policy and market rates is unavailable. A decoupling between the federal funds rate and market rates can occur at any time, meaning that even if the Fed lowers its policy rate to counter an economic downturn, market rates might remain stagnant or even rise, as seen in September 2024.

Cinderella After Midnight

Looking at the relationship between the Fed Funds Rate and the 10-Year Treasury Yield, it’s clear that despite a low Fed Funds Rate, the 10-year Treasury yield began to climb rapidly after 2020. This reflects inflationary expectations in the market (as per “the Fisher equation”: nominal 10-year Treasury yield = real interest rate + expected inflation). In simpler terms, the market is anticipating higher inflation in the future. While the threat of inflation might have seemed less significant since the 1990s, that’s no longer the case.

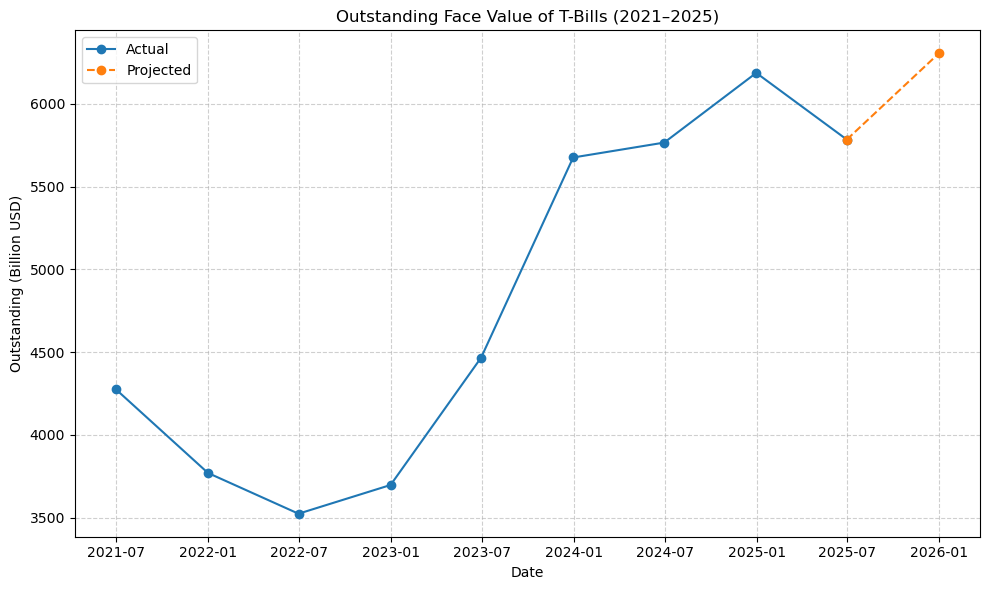

The reality after the “magic” of low inflation and easy money presents numerous challenges. The outstanding amount of Treasury bills (T-bills), short-term government debt, dramatically increased from about $3.7 trillion at the end of 2022 to $6.2 trillion by the end of 2024, with a further projected rise to $6.8 trillion by the end of 2025. A significant portion of these will mature by the end of this year and in early next year.

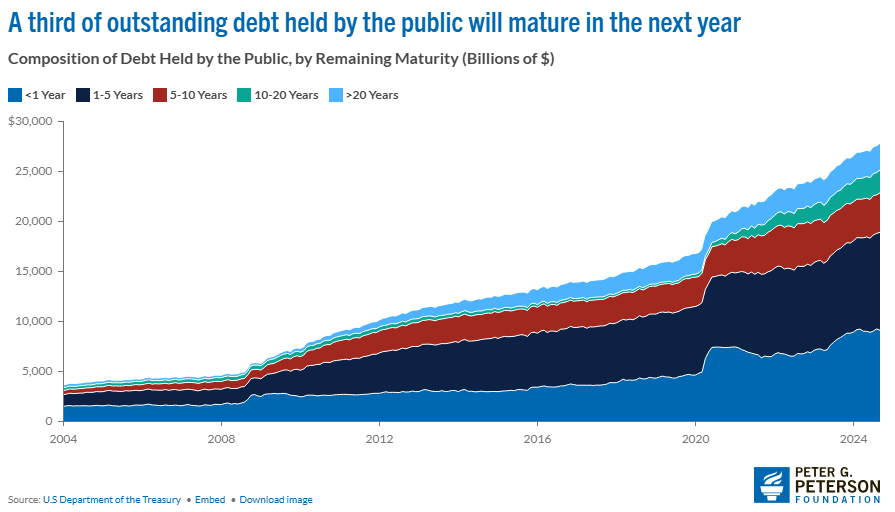

A staggering $9.3 trillion of all existing publicly held debt is scheduled to mature between April 1, 2025, and the end of March 2026. More than $3.1 trillion of this maturing debt was last issued two or more years ago, meaning it will likely need to be reissued at higher rates than before. The Congressional Budget Office anticipates that interest rates on longer-term securities will remain elevated compared to the previous decade.

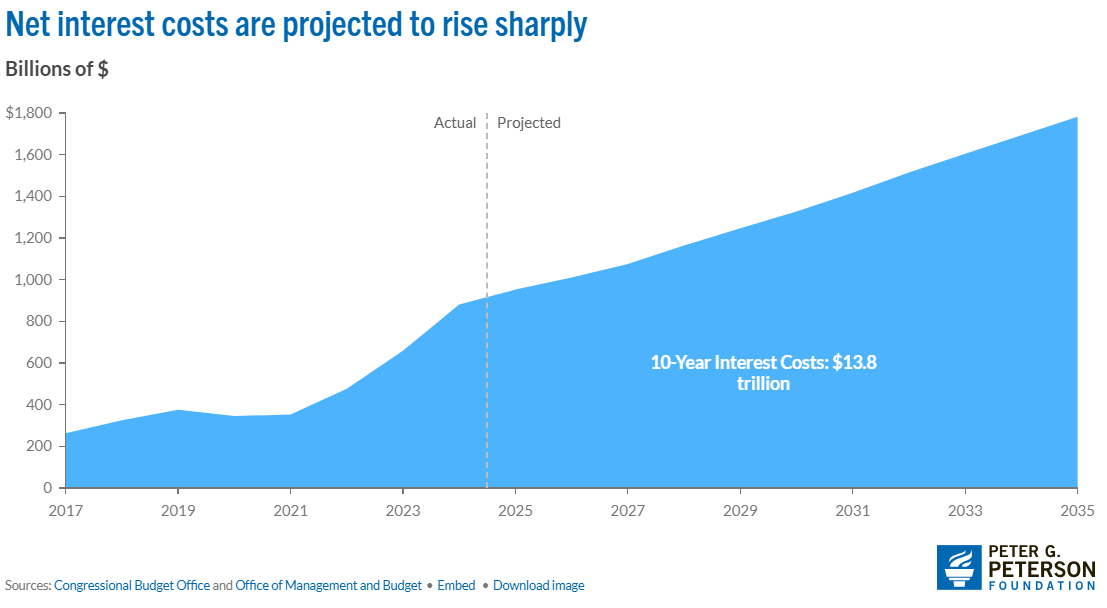

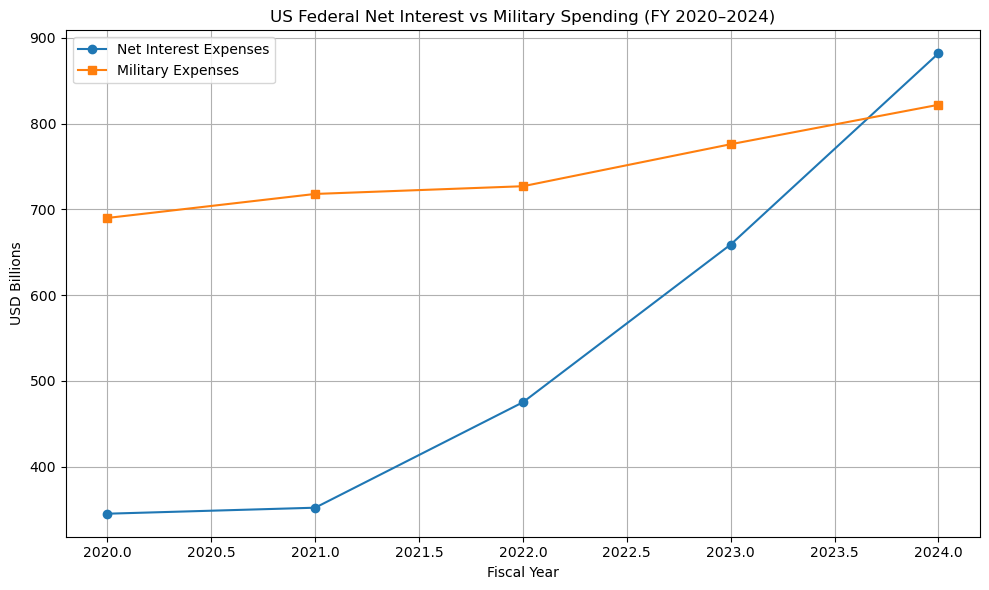

In total, federal net interest payments more than doubled in just three years, soaring from $352 billion in 2021 to $881 billion in 2024. These costs are projected to climb even further, reaching $952 billion in 2025 and exceeding $1 trillion annually by 2026. This would account for over half of the 2026 deficit and total nearly $14 trillion over the next decade. Remarkably, federal net interest payments have already surpassed military spending.

Ultimately, the pressing challenge is to lower market interest rates, which are showing a concerning upward trend. Several strategies exist to achieve this.

First, the Federal Reserve could reduce its benchmark interest rate. However, as previously mentioned, while the policy rate influences market rates, its impact can sometimes be very limited. Alternatively, the Fed could intervene by buying securities, injecting money directly into the banking system. Yet, all such policies hinge on the crucial assumption that inflation can be effectively controlled.

Second, fiscal policy, involving the government reducing its spending or increasing taxes, could indirectly influence the market. However, if the government simultaneously cuts spending and also reduces taxes, these effects would cancel each other out.

Third, large inflows of foreign capital into a country’s bond market can increase the supply of funds available for lending, thereby driving down interest rates.

Tug of War on Wheels

The contours of current political and international political economy events are beginning to emerge, though they remain somewhat blurry. It appears incredibly complex, especially with the collision of seemingly contradictory policies, making the true objectives unclear.

It’s like a “Tug of War on Wheels,” or seeing horses pulling a carriage in different directions. However, the carriage will eventually move in a single direction, and I believe that direction will be towards lowering market interest rates. While an initial objective might have been to reduce the trade deficit through high tariffs, the cost to American consumers is significant. More importantly, a decline in trust towards the U.S. during tariff negotiations directly impacts the bond market. Therefore, the application of high tariffs would likely be limited, and the direct revenue generated from them would not be substantial. Ultimately, high tariffs may become little more than a “wrapper.”

Consequently, the outcome of this “Tug of War on Wheels” — the substance beneath the wrapper — is likely to be large inflows of foreign capital, leading to lower market interest rates, managing public debt, and achieving political objectives.

Of course, this process will come with considerable costs, manifesting as increased economic volatility, geopolitical friction, and a potential erosion of multilateral cooperation. The trade order forged by the WTO and FTAs since the 1990s will likely weaken. Questions will undoubtedly arise regarding whether U.S. Treasury bonds and the dollar maintain their status as safe-haven investments. The relationship between the U.S. and its allies and partners, built on the dual goals of economic growth and security, will also face various doubts. These costs might be temporary, and the system could show resilience, eventually reverting to its previous state. However, the expenditures of this transitional period, from the Pax Americana to the formation of a new world order — a period of unknown duration — might only just be beginning.

References

Associated Press. (2021, July 22). Inflation is “transitory,” Powell says, and the Fed stands ready to adjust policy. AP News. Retrieved July 26, 2025, from [https://apnews.com/article/inflation-health-coronavirus-pandemic-business-6e7c813472a3eb706e0cdafe305c1477]

Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. Retrieved July 26, 2025, from [https://www.crfb.org/]

Fiscal Data (U.S. Treasury). Retrieved July 26, 2025, from [https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/]

Macrotrends LLC. U.S. trade deficit. Retrieved July 26, 2025, from [https://www.macrotrends.net/]

Peter G. Peterson Foundation. (2025). High interest rates left their mark on the budget. Retrieved July 26, 2025, from [https://www.pgpf.org/article/high-interest-rates-left-their-mark-on-the-budget/]

U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 26, 2025, from [https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/]

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved July 26, 2025, from [https://fred.stlouisfed.org/]